2023.10 KENDOJIDAI

Composition: Teraoka Tomoyuki

Photography: Suginou Shinsuke

Translation: Jouke van der Woude

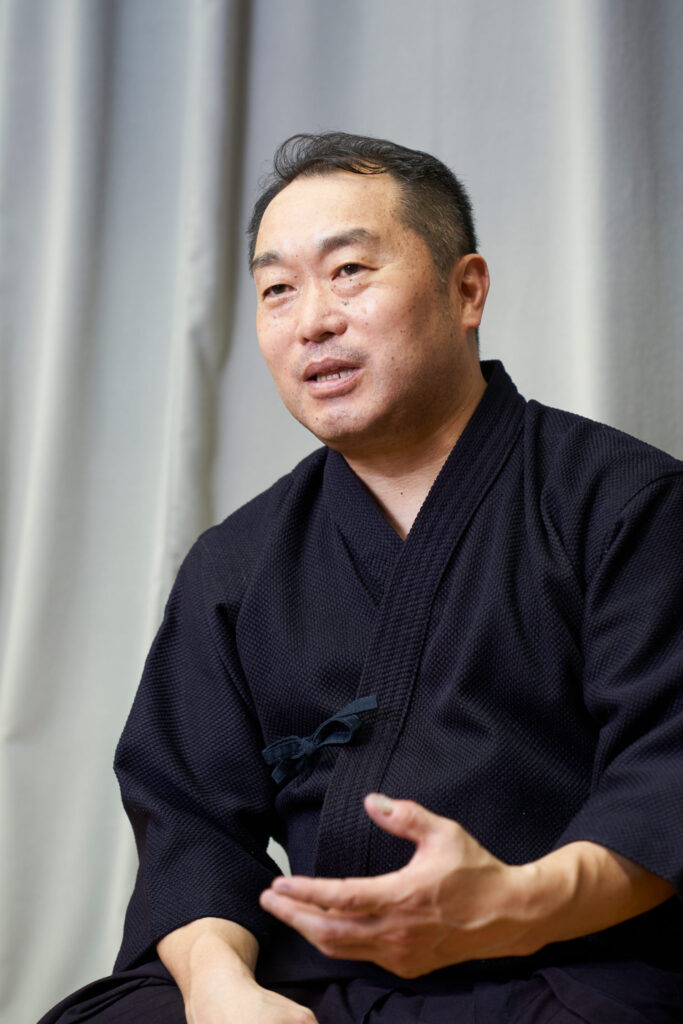

Suzuki Tsuyoshi has won the All Japan Kendo Championship title and currently mentors the next generation of practitioners in the Chiba Prefecture Police. He provided a clear explanation of the highly intricate technique known as Tame (roughly: build up). He stated, “To manifest Tame, one must enter into Aiki (a synchronous state with the opponent), and it is within this state of harmony that Tame creates opportunities for successful strikes.” In this article, Suzuki, an accomplished instructor, elaborates on the concept of Tame and the subsequent strikes which are followed through with (known as Uchikiri*).

*Uchikiri refers to the noun; follow-through. Uchikiru is the verb; to follow through

Suzuki Tsuyoshi, Kyoshi 8th Dan

Tame is a combination of Aiki and patience

The concepts of Tame and Uchikiri are undeniably complex and remain techniques that Kendo practitioners continuously strive to improve. As I am still on my own path of learning, I cannot be certain of how effectively I can convey these ideas, but drawing from my experiences as both a competitor and instructor, I would like to share my thoughts on Tame and Uchikiri.

In Kendo, it is often emphasized that the key is to make the opponent move. But, how can one move the opponent effectively? This is where the concept of Tame becomes crucial. When Tame influences the opponent’s mind, and that influence manifests in their movements, it creates an opportunity for a successful strike. Tame might sound like a highly complex notion, but I believe it consists of two elements: Aiki and patience. It involves harmonizing with the opponent, closing the distance while interacting, and both parties enduring without taking a step back. The one who loses in this contest of patience will be the first to make a move, providing the opponent with an opening for a successful strike.

Aiki is another ambiguous term similar to Tame, but in my view, it represents a state where both individuals are like tugging on a rope. When both sides are in this tense state of pulling on the metaphorical rope, even the slightest movement by the opponent becomes readily apparent. Both are actively seeking opportunities for a strike in this state of tension, and this is what Aiki means. Now, patience is about how long you can maintain this tensity in the metaphorical rope. Engaging in Shiai with high tension is demanding for both the mind and the body. Eventually, one of the opponents may succumb to the pressure and momentarily let their guard down. It is in that split second that an opportunity for a successful strike arises.

By practicing Aiki, one can truly experience Tame against any opponent

When I prepared for the 8th Dan examination, my focus during Keiko was on moving the opponent and reading their subtle mental and physical cues. Moving the opponent involves enduring in Aiki, creating a situation where the opponent moves first. In Dan examinations, I believe that the act of striking the opponent and achieving success are not necessarily aligned. This is because the examiners are not merely observing the act of striking but rather the entire process leading up to the strike, starting from mutual Seme.

To put it in simpler terms, in Shiai where one unilaterally strikes the opponent, even if the striker is considered strong, it would not be described as a good Shiai. In this scenario, achieving a higher Dan grade is unlikely. Passing the examination is more attainable when both participants engage in subtle, tense negotiations, affecting the opponent’s state of mind, breaking their composure, and seizing the opportunity to strike without hesitation.

If one can express this process effectively, the examiners are more likely to evaluate it as a good Tachiai, bringing you closer to passing the examination.

The timing of my 8th Dan examination overlapped with the Tokyo Olympics, a period when I couldn’t have Keiko at all. In the first place, after retiring as a Tokuren member and becoming an instructor, the frequency of my Keiko had drastically decreased, and I could only practice with adults once a week, if that. At such times, the only place where I could have Keiko every week was in the youth instruction at the Uenodai Kenyukai. Practicing for the 8th Dan examination in the youth instruction setting might seem impossible under normal circumstances. However, to aim for success, I had to make each practice as fulfilling as possible. So, even when having Keiko with young Kenshi, I focused on the principles of Aiki. Surprisingly, this turned out to be very productive. Naturally, there was a significant difference in ability between me and the young Kenshi. I could easily strike them if I wanted to, but instead of striking easily, we practiced harmonizing our feelings and attacking each other. As a result, I gradually became able to anticipate the movements in the hearts of the young Kenshi, and I started to feel the same sense of fulfillment as in adult Keiko.

In the actual examination, I was able to pass on my second attempt. The first attempt was chaotic, even I could tell, and it ended with me hastily putting away my Kendo Bogu right after the first round of examinations. But on the second attempt, I completed the examination with a sense of satisfaction. I could endure more than my opponent at the moment when I entered Shokujin no Maai (the Maai where blades touch), and I had the feeling that I could apply Tame and strike effectively.

Focusing on lower body action

If you have successfully influenced your opponent’s mind by applying Tame and identified opportunities for strikes, the next crucial step is to execute those strikes decisively. To master these decisive strikes, I practiced striking from Chikama (close Maai) in preparation for the examination.

As mentioned earlier, when you aim to practice Tame through endurance in Aiki, the distance inevitably becomes closer. Learning to drive the body forward and cut through the opponent from this distance was something I considered essential for success. Typically, we conduct Keiko on strikes from Toma (far Maai) or Issoku Itto no Maai. However, in a real fight, the situation might not always align with these distances. There could be instances where you sense an opportunity for a strike, but the opponent quickly closes the distance. In such cases, it’s important not to change your strikes just because the distance is close. Instead, I consistently practiced striking the opponent in a specific manner, regardless of the situation.

I often tell young Kendo practitioners that only practicing in your comfortable Maai is not enough. If you can only execute techniques in favorable situations, your opportunities for strikes will be significantly limited, and you won’t be able to progress in Shiai. By developing the ability to strike in any situation, your range of Kendo techniques will expand significantly.

So, how can you put Uchikiri like this into practice? In this regard, I believe that the lower body plays a crucial role. While it may be common to think that the upper body, including hand movements, is important for Uchikiri, I believe that the key elements for achieving Uchikiri are found in the lower body. Starting with a step from the left foot, driving the body forward from the waist, executing the strike, and immediately following up with the left foot to regain your posture. Only when you can perform this sequence swiftly can you execute Uchikiri, especially in Chikama. This is challenging, and that’s why I believe doing Keiko on strikes in Chikama is necessary.

Once you’ve mastered this sequence of movements, you’ll be able to enter your opponent’s Maai without fear. If you can get into Aiki with your opponent at that moment, it will likely lead to an Ippon recognized by everyone.

Kendo is a martial art that relies on interaction with others, and it only truly comes to life when there’s an opponent. It’s crucial not to become whimsical and to listen to the conversation through the Kensaki. The theme of Tame is precisely a technique born from the presence of an opponent, and by consciously striving to understand your opponent’s mindset during regular Keiko, it will be more fulfilling and inevitably lead to improvement. Furthermore, in your everyday life, considering how your actions affect others is essential. When this becomes second nature, it will be reflected in your Kendo practice, making it easier to understand your opponent’s mindset. I hope you’ll put these principles into practice.

Tame

The rest of this article is only available for Kendo Jidai International subscribers!