2022.6 KENDOJIDAI

Photography by Kunihiko Nishiguchi

Translation by Mariko Sato and Pepijn Boomgard

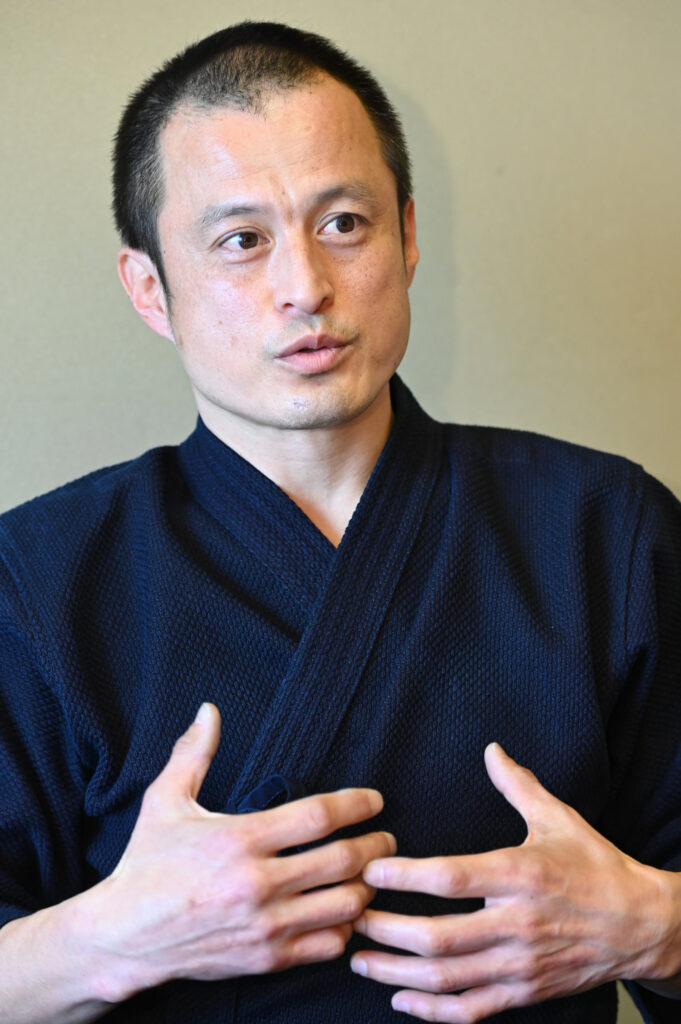

“I try not to be fixated on the centerline,” says Oda Masayoshi, Kyoshi.

Having had a long and distinguished career as a member of the Kanagawa Prefectural Police Kendo Tokuren, Oda Sensei transitioned into a teaching role after retirement. In November 2021, he successfully passed the 8th Dan examination. He shares that the words of his mentor, “Don’t try too hard to take the center” and “Have the spirit to yield,” led him to a deeper understanding of Aiki.

Oda Masayoshi, Kyoshi 8th Dan

The Seichūsen refers to the vertical line that runs through the center of the body. As a practitioner’s skill level increases, so does their awareness of this line. They strive to maintain their own balance along it while attempting to disrupt their opponent’s left fist or body axis positioned on this line.

This action is often referred to as “taking the center.” The Seichūsen is an essential element in the pursuit of taking center.

However, I try not to be overly conscious of the Seichūsen. Of course, taking the center is an important factor in achieving a valid strike. But I believe that a strong desire to “take the center” can easily turn into an attachment, which in turn leads to unnecessary tension and creates openings.

This tension often shows up in the way one grips the Shinai, especially with the right hand. When one becomes too focused on taking the center, it’s easy to unintentionally grip too tightly. A tight grip means that one must first release that tension before transitioning into a strike. Furthermore, that excess strength can be exploited, causing you to become fixed in place or lift your hands, making you vulnerable to a counterattack.

For that reason (though this is just description) if we think of “controlling the center” as a scale with a maximum value of 10, I try not to dominate it all by myself. Instead, I aim to allow about 60% to the opponent. I believe that this kind of mindset actually leads to better control of the center.

If you try to take all 10 points for yourself, the opponent will immediately sense that the center is being taken and respond by evading or countering. In some cases, they may even use your force against you.

I began thinking this way after receiving guidance from Miyake Hajime Sensei (former Kanagawa Prefectural Police Academy councelor), who taught me about the concept of the Shiburoku (40-60) No Kamae.

He said, “In competition, the mindset of ‘I’ll take the initiative’ may be important. But it’s just as important to have the spirit of yielding. That kind of attitude is not only useful in daily life, but it can also be reflected in Kendo.”

When engaging in the battle for the center, yielding 60% to the opponent does, naturally, lead to being struck more often. However, being struck is not necessarily a bad thing. For instance, I might reflect that I was correctly Dō because I executed a proper Men strike.

By continuing to train with this mindset—accepting being struck while maintaining a composed and forward-pressing spirit—I gradually began to feel more mentally relaxed. When the balance of control over the center is something like 5 or 6 for the opponent, and 5 or 4 for me, it creates a tense and finely tuned exchange.

I began to sense that this state of engagement leads to Aiki. Both I and my opponent can feel that we’ve “taken the center,” and that tension allows for a mutually committed, simultaneous encounter. To cultivate this state, I consciously practice with the mindset of Shiburoku No Kamae.

In the past, I trained as a member of the Kanagawa Prefectural Police Kendo Tokuren with the aim of becoming the best in Japan. Winning was expected of us, and I was filled with the desire to win and to strike. I also believed that simply stepping into Maai was a form of Seme.

However, such a strong mindset naturally led to strong, forceful pressure. When my drive to take the center became too overpowering, my opponents would retreat. I was often told that my Seme was “too strong,” but I struggled to correct it. As a result, there were many instances where no decisive conclusion could be reached in a match.

After learning the concept of Shiburoku No Kamae, my awareness of the Seichūsen changed, and so did my Kendo. I’ve come to feel that having the spirit to yield to the opponent is also part of what makes Kendo what it is.

Don’t Over-Focus on the Center Line

In order to put the aforementioned Shiburoku no Kamae into practice, I believe it is essential to adopt a natural, relaxed Kamae—one that places no unnecessary strain on the body—and to develop proper Tenouchi.

Personally, I try to use variations in rhythm and intensity to provoke the opponent’s intention to strike, then respond by applying pressure or delivering a strike myself. While yielding 60% of the center in the contest for control inevitably involves risk, I’ve found that as long as I have a solid grasp of Maai, I won’t be struck easily.

Of course, it is still necessary to apply pressure (Seme). Rather than focusing on attacking with a single “point” from the tip of the Kensen, I aim to press forward with the entire “surface” of my body. Even if the opponent appears to have taken the center, if I apply pressure using my whole body as a surface, they will still feel it. I believe this is where the key to winning in a tense, finely balanced match lies.

A few years ago, I was reviewing my Kamae in front of a mirror in an effort to practice Shiburoku no Kamae. I realized, to my surprise, that my right hand was more extended than I had thought, and my posture leaned slightly forward. It wasn’t the stance I had imagined. Since then, I’ve made a habit of occasionally checking and adjusting my Kamae in the mirror.

In particular, to correct my forward-leaning posture, I began to open my chest and adopt a larger Kamae. At first, it felt unnatural and made movement somewhat difficult, but it brought about some very positive changes. One of the first things I noticed was a shift in my line of sight. By straightening my posture, my field of vision widened, and more importantly, I became more aware of the weight being properly placed on the ball of my left foot. This gave me a greater sense of mental composure.

With that composure came a shift in how I perceived the Seichūsen. My mindset became, “If you want to take the center, go ahead—I’m pressing forward too.” That kind of quiet confidence helped eliminate unnecessary tension, allowing me to stop trying to suppress my opponent’s kensen with arm strength. Instead, I found myself applying pressure through the “surface” of my body, as mentioned earlier.

Letting Them Think They’ve Taken the Center

The rest of this article is only available for Kendo Jidai International subscribers!