2024.4 KENDOJIDAI

Photography: Nishiguchi Kunihiko

Translation: Pepijn Boomgaard

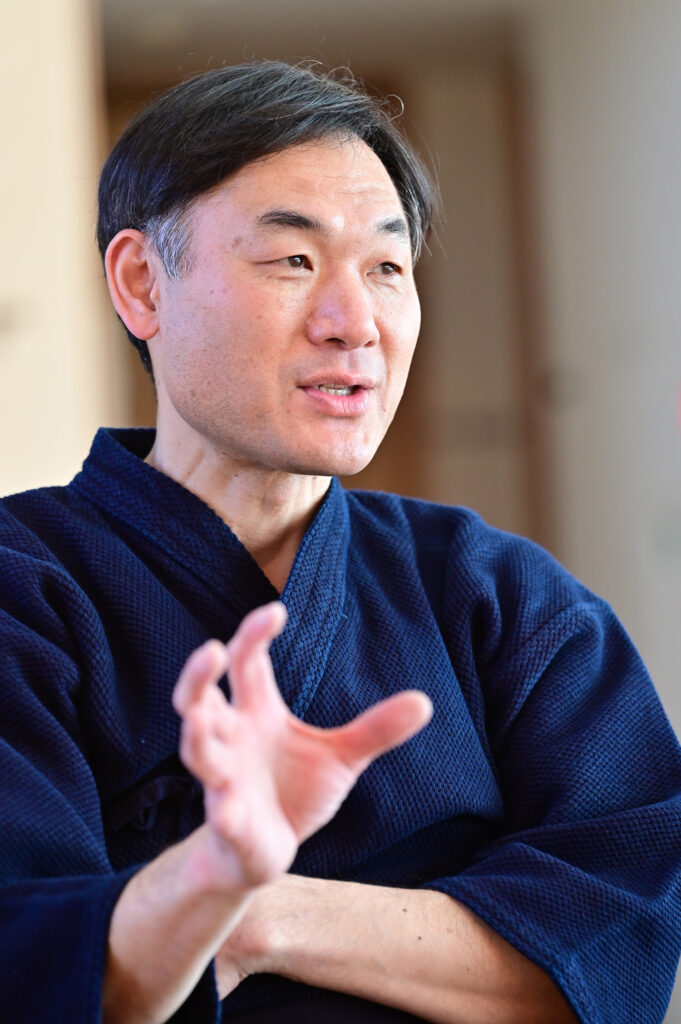

Iguchi Kiyoshi, a successful Kenshi ever since his younger days, passed 8th Dan in 2016. While preparing for his examination, he realized the importance of taking the initiative.

Iguchi Kiyoshi (Kyoshi 8th Dan)

There are a number of thoughts on initiative. When teaching children, we often tell them that it means “to strike first.” This is not wrong, but as the level of proficiency increases, the meaning of “initiative” changes slightly.

In Kendo, we can divide initiative in Sen and Go No Sen. Sen is when you strike first. Go No Sen is striking after the opponent attacks.

There is also the teaching of Mittsu No Sen*. Of these, Ken No Sen and Tai No Sen are the same as the aforementioned Sen and Go No Sen. Tai Tai No Sen is about engaging your opponent and approaching each other, finding an opening, and using your sword, body, feet, or mind to take the initiative and win. There is also the teaching of Sen Sen No Sen, in which you strike as a sign of your opponent’s intention to move appears.

I believe that taking the initiative is about facing the opponent, taking the upper hand, and reacting quickly to their movements in order to score. Even if you do not make the first move, you gain the upper hand through your spirit or your Kensen, and you are able to react immediately the moment your opponent moves. I think that this image is important.

However, the moment when you are about to strike is called Okori, which provides your opponent with an opening. Your opponent will be aiming for moments such as these, so it’s important to read your opponent. If you can understand what your opponent is aiming for and respond accordingly, maintain your superior position, and apply your techniques, it could be said that you have taken the initiative.

As you get better, you will be able to perform these actions unconsciously. In addition, you will be able to make the right decisions and naturally take the initiative in tense situations such as matches or examinations. I already mentioned that in order to take the initiative, the ability to read your opponents is necessary. In Kendo, the opportunities to strike are: (1) at the start of your opponent’s movement (Okori), (2) after your opponent blocks an attack, (3) after your opponent finishes their attack, (4) when your opponent stops moving, (5) when your opponent steps back, (6) when your opponent’s mind is disturbed, and (7) when your opponent has lost the essence of reality and has become empty (when your opponent loses focus or becomes careless). I believe that out of these, the moment your opponent is about to move is the most important. Whenever someone moves forward, moves back, tries to do something and stops, or tries to make their next movement, openings appear.

If you push forward on the assumption that your opponent will fall back, but the opponent does not feel threatened and instead takes over, it is just selfish Seme on your part. This is not taking the initiative. Instead, you lost it.

Based on the flow of the match, movements, and feelings, you can read how the opponent reacts to your movements, and choose your own techniques based on accurate judgment. Therefore, it is necessary to take these points into consideration when practicing. Don’t just strike. The ability to read your opponent will allow you to take the initiative. It will also lead to Kendo based on ”principles*.”

Practice applying pressure from a closer distance than usual

I passed my 8th Dan examination at my third try. At my 6th and 7th Dan exams, I relied more on speed and unilaterally applying pressure, breaking down my opponent, and striking.

As I approached my first 8th Dan examination with this mindset, I was aiming to push and break down my opponent’s Kamae, and striking when they weren’t able to do anything. However, it is extremely difficult to do this when facing someone of a similar skill level. The opponent is also trying to break you down. I lacked the ability to read my opponent’s moves and deal with their response to my Seme.

I was still young and confident in my speed and physical strength, so that’s what I relied on. When I realized this style of Kendo wouldn’t cut it, I began to think about how I could make my opponent attack. In my conventional style of unilaterally pressuring and attacking, the timing of my strikes was too fast and my opponent saw through it. That’s why I failed twice.

Therefore, I began to think about how to draw out my opponent. In order to make the opponent feel like striking, patience and Tame are necessary. At the same time, because you are fighting at a dangerous Maai, the risk of being struck also increases. However, if you are afraid of being hit, you will not be able to get a satisfying Ippon. I was especially conscious of Go No Sen. This is not just about waiting. I suppressed my desire to strike and seized the opportunity the moment my opponent moved forward, and placed great importance on striking Debana or using Oji-waza.

For example, when your Seme is too strong when fighting your opponent, they might become wary and won’t feel like attacking. However, if you lose focus and simply wait, you will be too late. That is why I’ve come to emphasize the following two points:

- Be ready to strike at any time, but stay patient until the opponent makes a move.

- Refrain from striking from the far distance from which you used to be able to strike and take half a step more from Issoku Itto No Maai.

Since it is important not to make any mistakes in a match, there is a tendency to avoid fighting at a high-risk Maai. However, I think this is important for high-level practitioners seeking Kendo based on “principles.”

Carefully consider the opponent’s intentions and avoid unnecessarily striking

In order to achieve Kendo based on principles, it is necessary to eliminate unnecessary strikes during training. When we perform a technique, we do it with the intention of making a valid strike (Yuko Datotsu). In this process, the aforementioned “patience” and “stepping in further than Issoku Itto No Maai” are important. When someone is still inexperienced, they tend to just perform techniques without considering their opponent’s movements. In this case, they will often be drawn out by their opponent to attack, and the strikes will be useless. Efforts should be made to eliminate such Seme and striking.

Naturally, many mistakes will be made during practice. However, if you do not put effort into the process of reading your opponent’s moves, breaking them with Seme, and making the conscious decision to strike, you will just repeatedly strike unnecessarily.

In order to avoid unilateral Seme, we must find out what kind of moves our opponent will make in response to our Seme. This is what leads to Seme-ai, or mutual Seme. Observe the opponent’s slightest movement to find out what their intention is. I often look at the movements of their hands and body.

The slightest movement of the opponent’s Shinai, whether it is towards Ura or Omote, also affects this judgment. Keeping the opponent’s movements in mind, we must exploit their intentions.

For example, when the opponent is aiming to strike Debana, let them strike and then use Oji-waza, or take over their strike with your own. Or move your Kensen to make your opponent think you are going for Men. It is crucial to read the opponent’s slightest reaction to your smallest movements.

You won’t be able to shift your weight when the Maai is close, as your center of gravity will be on your right foot. Your center of gravity must be balanced so that you can move. Only then can you and your opponent pressure and read each other. In this subtle duel of Kensen, knowing whether your opponent is feinting or really coming to strike comes with the experience gained through many years of practice.

Move your opponent and strike

When we try to strike from a distance closer than Issoku Itto No Maai, the opponent will first try to deal with it by stepping back. Even if your opponent steps back, it is important to pressure them with the image of hitting their Men-buton. Even if the strike does not end up being valid, being almost struck will feel as a threat to the opponent.

In many cases, an opponent who has been hit by such a strike will try to recover and land their own strike. When the opponent feels like attacking back, you can turn this mentality into an opportunity to strike Debana or use Kaeshi-do.

Reading the opponent’s moves based on the flow of the match is an important factor.

For example, if you have been mainly aiming for Men during the match, and you show the intention to strike Men, your opponent will reveal that they were waiting for you to strike Men so that they could do Kaeshi-do. If you can anticipate this movement and strike Kote the moment they move, you will have taken the initiative. This kind of insight is necessary.

It is difficult to read the signs that your opponent is about to make a move, but it is impossible for the opponent to win without striking, so they will always end up moving. However, if they are not convinced that they can strike, they won’t move. It would be ideal if you can create a situation in which your opponent has no choice but to make a move, and then seizing the opportunity when you catch the first sign of such a move. No matter who the opponent is, if both players are overly cautious, neither will hit Ippon. I think that overcoming the risk of being struck is what leads to taking the advantage.

Entering further than Issoku Itto No Maai, making the opponent move, then striking Men.

Let the opponent strike Debana-men and perform Kaeshi-do.

When the opponent shows they are aiming for Kaeshi-do, strike Kote.

When your opponent stops moving, hit Tsuki.

Translator’s Notes

Mittsu No Sen: The three types of initiative. Ken No Sen (attacking first) , Tai No Sen (waiting for your opponent’s attack and then striking), and Tai Tai No Sen (answering the opponent’s attack with an unwavering strike).

Principles: Following Riai, the underlying principles of Kendo.