2008.1 KENDOJIDAI

I was asked to write my personal history in Kendo. As a person who is still in the process of training, I have not had the time to look back over my life, but have only been moving forward. In addition, I have no significant Kendo-related accomplishments or achievements, so I have been hesitant to publish this as a personal history. However, my life as a Kendo practitioner has been guided and nurtured by the history of my predecessors, who struggled to build the Kendo world of today in the turbulent times before and after World War II. As it is now fifty years since I set out to become a professional Kendo instructor, I thought it would be helpful to look back on my own humble life in Kendo to help further my training, and also to provide some kind of reference for younger students who are training in today’s blessed environment.

Sato Nariaki, 8th Dan Hanshi

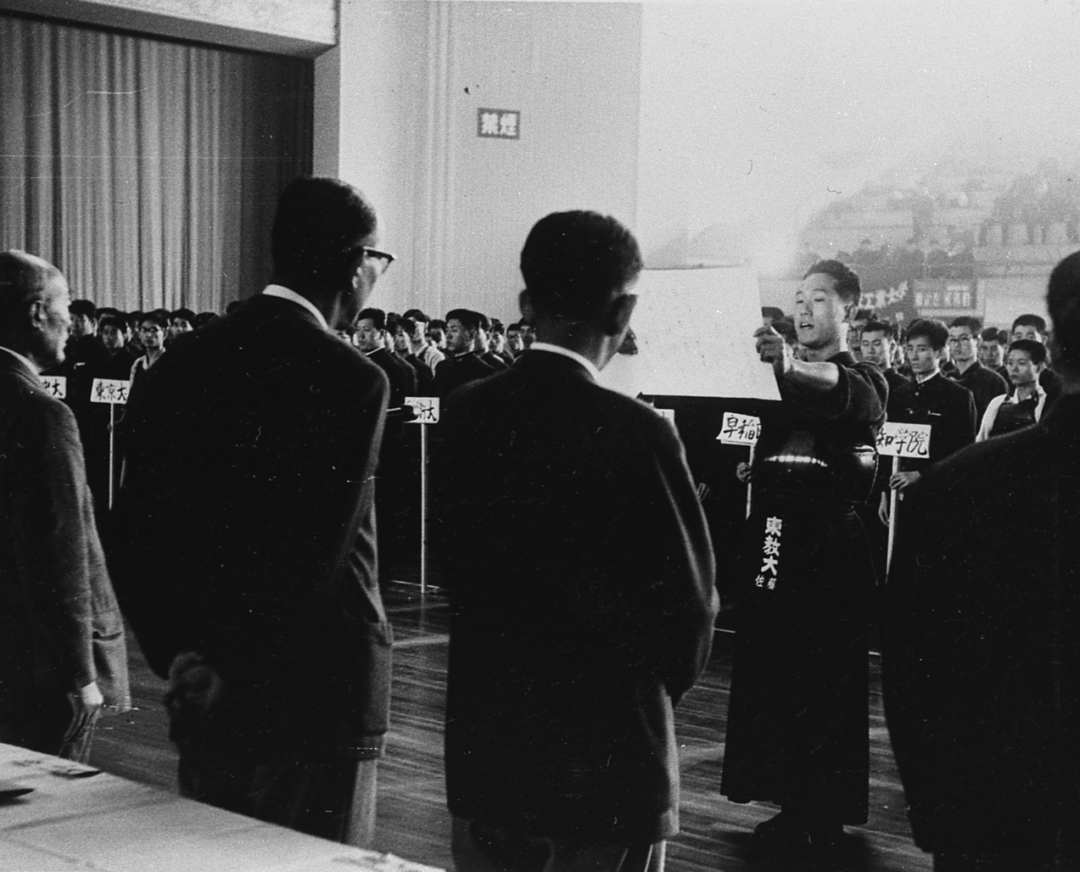

Born in Tochigi Prefecture in 1938, 82 years old. After graduating from Utsunomiya High School, he went on to Tokyo University of Education, where he majored in physical education, and then to the Graduate School of Education. After working as an assistant professor at Komazawa University, he became an instructor at his alma mater, Tokyo University of Education, before retiring as a professor at Tsukuba University in 2002. He has participated in the All Japan Championships, the World Championships, the National Athletic Meet, the National Teachers’ Meet,and the All Japan East-West Tournament. He is currently a professor emeritus at Tsukuba University. Acting President of the All Japan Student Kendo Federation.

Famous names at Utsunomiya Futazatoyama Dojo

In 1954, I entered Tochigi Prefectural Utsunomiya High School and joined the track and field team, but I could not bring myself to train at all. Naturally, my record did not improve. One day, while I was agonizing over my declining academic performance, my father said, “Let’s go to Kendo!” He took me to the Futazatoyama Dojo, which was located in the mountains behind the prefectural office. At that time, the Dojo held monthly Keiko sessions with many teachers including Iwase Hokotaro, Yatagai Yoshiharu, Yomogida Kiichi, Ogasawara Saburo, Kanazawa Kenichiro, Tasaki Yusuke, Abe Shin, Kotake Toshio, Kurogo Umeo, Noguchi Shizuo, Taguma Shinetsu, and Horiuchi Shokichi, as well as the Utsunomiya Kendo Federation. Kojima-sensei, who had been repatriated from Manchuria and was working on cultivating the highlands of Takahara mountain, sometimes joined us. He usually stayed at our house on those occasions. He wore white pants and Kendogi. That was the beginning of my Kendo life. Although I was clumsy, I tried my best to practise. There were many times when I was encouraged by the praise of the teachers around me.

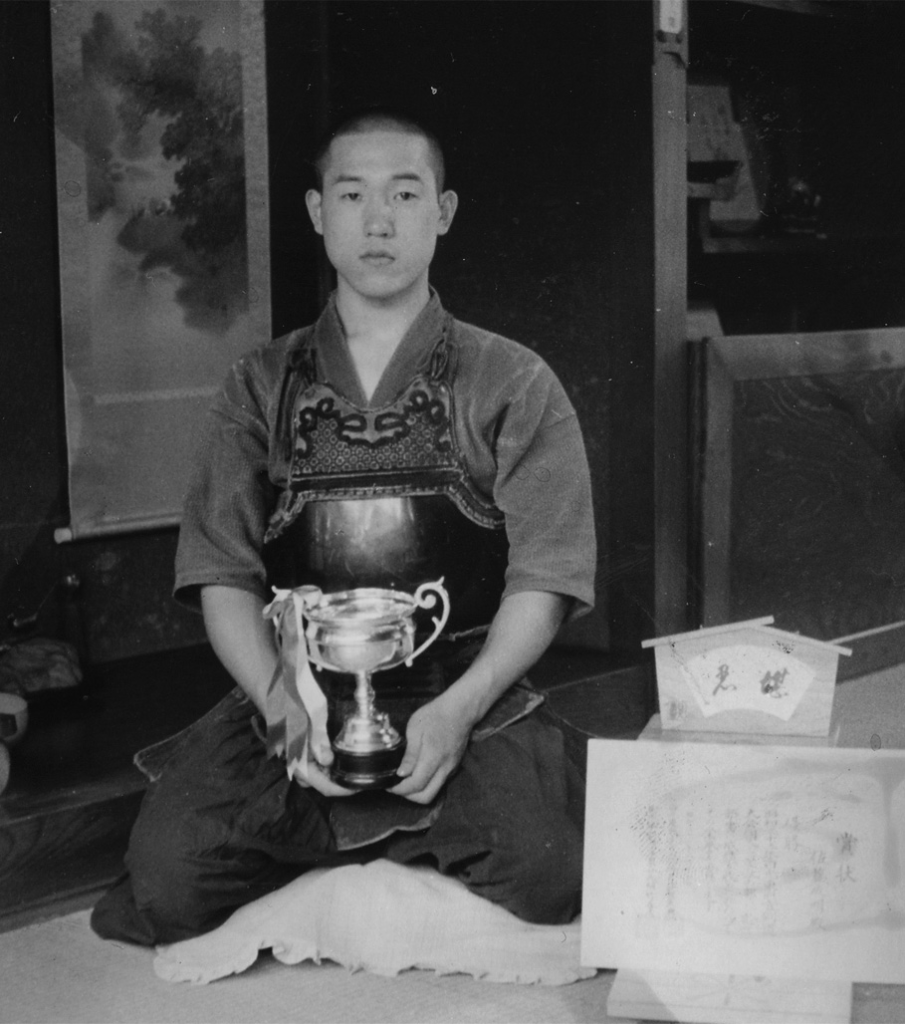

In my second year of high school, although we were allowed to revive the Kendo Club, I couldn’t make the team for competition. Even when I participated in individual competitions, I lost many fights in a row (only once did I come in third place in an individual competition at a rookie tournament). In my third year, we finally had five members, and we won the prefectural preliminaries for the Kanto Tournament for the first time, defeating Imaichi High School, which my father coached. In the actual Kanto Tournament in Gunma, we were naturally eliminated in the league stage. Fortunately, we were able to participate in the 3rd National High School Kendo Tournament held in Aizu Wakamatsu City because we won the prefectural preliminaries. Of course, the result was that we were eliminated in the preliminary league.

There was a strict rule for the athletic activities at the school that we could practise on campus three days a week for no more than one hour a day. It was a challenge to get a total of 50 minutes of Keiko. What we lacked in on-campus practice, we made up for by attending Ogasawara Saburo Sensei’s Takefukan Dojo. I received guidance from many instructors, including the Dojo director, Kasuta Toshio (former president of the Tochigi Kendo Federation) who was the head for the younger generation, and Nojiri Yoshio Sensei.

Looking back on those days, the environment in which Kendo was practised, or rather the way it was viewed by those around me, was not always favorable, but rather negative and cold. I was even subjected to words of abuse such as “revival of militarism”, “feudalism”, “restorationism”, “right wing”, and “barbarism”. It may be hard to imagine for today’s students, but it was common for school clubs to be small and reserved in renting practice space, and sometimes we even practised on the dirt of the schoolyard.

However, in the midst of all the criticism and slander, I also heard some positive comments about Kendo from other quarters, such as “Kendo is the way to go, young people who do Kendo are wonderful”, “Kendo is the heart of Japan”, and “Kendo teaches moderation, politeness and respect”. I wrote such things in my diary at that time and I dare to write them down here now without hesitation.

Entering Tokyo University of Education

The impossible comeback victory

The rest of this article is only available for Kendo Jidai International subscribers!